A dismount in gymnastics is the move performed at the end of a routine on an apparatus, signaling the completion of the exercise. It involves a controlled exit from the equipment, aiming to precisely land on the floor.

Each apparatus has unique dismount requirements, and gymnasts aim to stick the landing—landing without moving the feet—to maximize their scores.

What Judges Look for Dismounts?

In gymnastics, judges evaluate dismounts across several criteria, focusing on the skill’s difficulty, execution, and landing. Since the dismount is the final element of a routine, it can significantly impact a gymnast’s score, both positively and negatively.

1. Difficulty Level

Higher-difficulty dismounts, such as those with multiple flips, twists, or a combination of both, increase the difficulty score (D-score). Judges look at how challenging the skill is and reward more complex dismounts accordingly.

Judges assess whether the dismount difficulty is aligned with the complexity of the rest of the routine. For instance, an elite-level routine typically ends with an equally high-difficulty dismount.

2. Execution and Technique

Judges evaluate the gymnast’s form during the dismount, including body alignment (straight for layouts, compact for tucks), leg position, and hand or foot placement. Points are deducted for bent knees, flexed feet, or an arched back in skills where a tight form is expected.

For flips and twists, judges look for precise, clean movements. Over-rotating or under-rotating can lead to deductions, as can incomplete or excessive twists. Smooth and controlled rotations show that the gymnast is in full command of the skill.

3. Height and Distance

The height of the dismount, or amplitude, shows the gymnast’s power and control. Judges reward high dismounts that demonstrate a strong push-off and good technique.

Judges also consider how far the gymnast travels horizontally from the apparatus in skills like bar and beam dismounts. Dismounts that land too close or too far from the apparatus can lead to deductions, as they may indicate issues with power or control.

4. Landing Control and Sticking

A “stuck landing,” where the gymnast lands cleanly without taking extra steps or movements, is ideal. Sticking the landing shows control and precision, and judges reward it. Any hops, steps, or wobbles on landing typically result in deductions.

Proper landing mechanics—landing with knees slightly bent, feet together (or shoulder-width apart when appropriate), and maintaining balance—are critical. Judges will deduct for any form breaks like an excessively low squat or off-balance position.

Common Deductions on Gymnastics Dismounts

Judges apply deductions based on the following common mistakes:

- Landing deductions: Steps, hops, or balance checks (0.1–0.3 per small movement; larger deductions for major steps or falls).

- Bent knees or flexed feet: Each counts as a small deduction (typically 0.1–0.3 per form error).

- Under or over-rotation: Deductions apply if the gymnast cannot control the landing due to rotation issues.

- Incomplete twists: If a twist isn’t fully completed, the gymnast may receive execution deductions and even lose difficulty credit if severely short.

- Leg separation: Unintentional leg separation during flips results in deductions (usually 0.1–0.2).

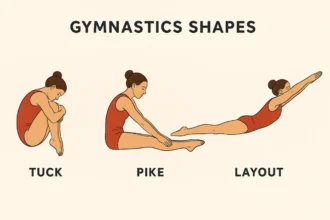

- Body shape deviations: Shifts from the intended tuck, pike, or layout body positions during rotation are also deducted (typically 0.1–0.3).

Types of Dismounts by Apparatus

Each apparatus has its own set of common and advanced dismounts, requiring unique skills and strengths. Below is a breakdown of dismounts based on apparatus:

Balance Beam Dismounts

Balance beam dismounts are among the most technical and challenging skills in gymnastics.

The balance beam, measuring just 10 centimeters (approximately 4 inches) wide and elevated 125 centimeters (about 4 feet) above the ground, adds an extra layer of difficulty to executing the final move of the routine. A gymnast must dismount from this small surface area while maintaining form and balance, often flipping or twisting mid-air before landing.

Here’s a closer look at some of the most common dismounts on the balance beam.

- Roundoff Dismount: A roundoff off the end of the beam, often followed by a flip for increased difficulty.

- Cartwheel to Tuck Salto: After a cartwheel on the beam, the gymnast tucks their knees and performs a backward flip.

- Back Layout with a Full Twist: A straight-body flip with a full twist, commonly seen in advanced routines.

- Gainer Dismount: The gymnast moves forward along the beam but performs a backward flip, often in a tuck, layout, or pike position.

- Double Back Dismount: An elite-level skill that involves two consecutive backward flips, requiring significant height and control.

Uneven Bars Dismounts

The uneven bars, with one bar set lower and another positioned higher, allow gymnasts to demonstrate aerial skills, flips, and twists during their dismount.

Since the gymnast must release from a swinging motion, they rely heavily on timing, grip, and body control to execute a successful landing. The difficulty of these dismounts often comes from the height and speed gained during the routine.

- Flyaway: A basic backward salto off the high bar, usually performed in tuck, pike, or layout positions.

- Double Back Tuck: Two consecutive backward flips in a tucked position, requiring powerful rotation.

- Double Layout: Similar to the double back but with a straight body position, demonstrating control and strength.

- Full-Twisting Double Back: A double flip with a full twist, showcasing coordination of twisting and flipping simultaneously.

- Toe-On to Double Front: A unique forward-flipping dismount that starts from a toe-on grip, commonly performed in a double forward flip.

- Piked Double Back: A double backward flip in a pike position, adding difficulty due to the straight legs bent at the hips.

Parallel Bars Dismounts (Men’s Gymnastics)

Parallel bars dismounts involve swinging or release moves off the bars, usually ending with dynamic flips or twists.

The parallel bars are positioned about 200 centimeters (approximately 6.5 feet) off the ground, and the gymnast’s final move often involves releasing from the bars with a combination of flips, twists, and rotations.

The challenge lies in maintaining form and executing the dismount cleanly, despite the momentum generated during complex swinging and flipping maneuvers.

- Double Back Tuck/Pike: A backward double flip performed in a tuck or pike position.

- Double Front: A forward double flip off the bars, demanding strong forward rotation.

- Double Back Layout: A double backflip with a straight body, requiring the gymnast to control rotation without tucking.

- Full-Twisting Double Back: A backward double flip combined with a full twist, adding complexity through rotational and twisting elements.

- Hecht Dismount: A swing release dismount involving a forward salto, often performed with a twist or in a layout position for added difficulty.

High Bar Dismounts (Men’s Gymnastics)

The high bar, elevated at approximately 2.8 meters (around 9 feet) above the ground, offers gymnasts the chance to build tremendous momentum through swings, releases, and grips.

High bar dismounts in men’s gymnastics are similar to those in women’s uneven bars but often performed with more force and complexity. Executing a flawless high bar dismount requires a precise blend of timing, aerial awareness, and body control.

The most common and spectacular dismounts on the high bar:

- Flyaway: A simple backward flip dismount often used by beginner-level gymnasts.

- Double Back Tuck/Double Layout: Two flips off the bar in either a tucked or straight body position, demanding height and control.

- Triple Back: An elite dismount featuring three consecutive backward flips, requiring tremendous height and rotation.

- Double Twist: A double flip with two full twists, showing exceptional control over both rotation and twisting.

- Full-Twisting Double Layout: A double layout with a full twist, often one of the highest-scoring dismounts due to its complexity and required control.

Rings Dismounts

Dismounts on the rings are particularly challenging because the gymnast must transition from a static hold or swing into a controlled release, often involving flips or twists.

During the dismount, the gymnast releases the rings, transitioning from a controlled swing or stationary position into a high-flying flip, twist, or rotation before landing. These dismounts are often complex and thrilling, requiring both height and impeccable timing.

The most common dismounts on the rings:

- Double Back Tuck: A common rings dismount, where the gymnast performs two backward flips in a tucked position.

- Double Layout: Similar to the double back but with the body held in a straight position, demonstrating control and power.

- Full-Twisting Double Back: A double flip combined with a full twist, requiring precise timing and strength.

- Double Front: A forward double flip dismount, challenging due to the need for forward rotation control.

- Triple Back: An elite dismount featuring three consecutive backward flips, showcasing extraordinary strength and height.

Floor Exercise Dismounts

In floor exercise, tumbling dismounts aren’t traditional “dismounts” but rather the final tumbling pass that closes a routine with power and precision. Unlike apparatus-based dismounts, tumbling dismounts take place on a spring-loaded floor that allows gymnasts to generate significant height and perform complex flips, twists, and rotations.

These final tumbling passes often determine the routine’s difficulty score and leave a lasting impression on judges and spectators alike.

Here are some of the most common and advanced types of tumbling dismounts in floor exercise:

- Double Back Tuck/Double Layout: Two flips in a tucked or straight position. Often performed as the last tumbling pass to demonstrate control.

- Full-Twisting Double Back: A backward double flip combined with a full twist, challenging due to its rotational complexity.

- Triple Twist: A single flip with three full twists, showing excellent twisting speed and control.

- Double Arabian: A half twist into a double front flip, adding variation and complexity.

- Quadruple Twist: A high-difficulty skill involving four full twists, achievable only by elite gymnasts with strong aerial awareness.

Essential Techniques for Gymnastics Dismounts

Mastering a dismount is vital for a gymnast, as it not only concludes a routine with finesse but also contributes significantly to the final score.

Here are the essential techniques that can help gymnasts achieve a perfect dismount across various apparatuses.

1. Proper Takeoff Mechanics

A successful dismount begins with a strong takeoff. Whether it’s a push-off from the bars, a leap from the beam, or a launch off the vault table, the takeoff determines the height, distance, and rotational momentum of the dismount.

- Arm Push-Off (Bars and Vault): A powerful push from the arms helps generate the height and distance needed. Gymnasts should engage their shoulders, core, and legs to maximize the force generated.

- Leg Drive (Beam and Floor): A strong push from the legs during a beam dismount or floor tumbling pass is crucial for elevation and control.

- Focus on Timing: Precise timing is essential for a smooth, controlled takeoff that maintains momentum without stalling mid-air.

2. Body Positioning and Core Tightness

Maintaining a tight core and controlled body position during flight is essential for performing flips, twists, and landings with precision. A well-controlled body position minimizes deductions and allows for a fluid dismount.

- Body Shape: Gymnasts typically maintain a tight tuck, pike, or layout position depending on the skill. Each shape has specific body alignment requirements that help in performing rotations effectively.

- Core Engagement: Keeping the core tight stabilizes the body and allows for smooth rotation, preventing flailing or unwanted body movements.

- Arm and Leg Control: The arms and legs should be kept in line with the torso to maintain control. Straight legs and pointed toes are especially important to avoid execution deductions.

3. Generating Rotational Momentum

Rotational momentum is the foundation of complex flips and twists in gymnastics. By generating sufficient momentum during takeoff, a gymnast can complete rotations with greater control and precision.

- Initiate Rotation Early: The gymnast should initiate the rotation as soon as they launch off the apparatus, using their arms and legs to set the momentum.

- Controlled Speed: For multiple rotations, controlling the speed is key. Gymnasts need to find a balance where they rotate quickly enough to complete the skill but not so fast that they lose control.

- Using Hips for Flips: In skills like tucks or pikes, drawing the knees toward the chest or bending at the hips generates faster rotation, while a layout position requires body tension to control the rotational speed.

4. Twist Initiation and Control

Twists add a layer of complexity and difficulty to dismounts. To execute twists correctly, gymnasts need to understand how to initiate, control, and complete twists with precision.

- Shoulder and Hip Engagement: Twisting requires the simultaneous engagement of the shoulders and hips. The gymnast initiates the twist by turning the shoulders and then follows with the hips, keeping the core tight to maintain alignment.

- Head Positioning: The head should remain in line with the body to avoid off-axis twists or loss of control.

- Gradual Increase in Twist Speed: For advanced skills, twisting should be smooth and gradual. Gymnasts often start with a half or full twist before progressing to double or triple twists, focusing on maintaining control at each step.

5. Visual Spotting for Landings

Spotting, or visually locating the landing area during flight, is a technique used to improve landing accuracy and stability. Spotting helps gymnasts prepare for the landing, enhancing their ability to stick it cleanly.

- Identify a Spot Early: In a flip or twist, the gymnast should identify a spot on the floor or landing area as early as possible.

- Adjust Body Position Mid-Air: Visual spotting allows the gymnast to make minor mid-air adjustments to prepare for a stable landing.

- Focus on the Landing Surface: By focusing on the landing area, gymnasts improve their ability to anticipate impact and absorb the force upon landing.

6. Absorbing Impact with Proper Landing Technique

A successful landing requires control and stability. The goal is to absorb the landing impact gracefully while avoiding any extra steps or balance adjustments that could lead to deductions.

- Bend the Knees Slightly: A slight knee bend upon landing helps absorb impact, providing stability and preventing knee strain.

- Maintain a Balanced Stance: The feet should be shoulder-width apart for a stable base, allowing the gymnast to hold the landing without wobbling.

- Use Core Muscles for Stability: Engaging the core muscles upon landing helps maintain balance, avoiding any forward or backward shifts.

Putting It All Together

Combining these techniques results in a successful, controlled dismount that meets the requirements of form, execution, and confidence. Each dismount skill builds on these foundational techniques, allowing gymnasts to perform complex flips and twists with precision.