In artistic gymnastics, the apparatus used by men and women differ dramatically. While both genders perform on floor and vault, the rest of the lineup is entirely gender-specific—something rare in Olympic sports. Let’s explore how we got here—and whether it could ever change.

What the Line‑Up Looks Like Today

Men’s Artistic Gymnastics (MAG)

- Floor Exercise

- Pommel Horse

- Still Rings

- Vault

- Parallel Bars

- Horizontal Bar

Women’s Artistic Gymnastics (WAG)

- Vault

- Uneven Bars

- Balance Beam

- Floor Exercise

Only two apparatuses—vault and floor—are shared, but even those are performed differently.

- Vault: The table is 10 cm lower for women (1.25 m vs. 1.35 m).

- Floor: Women must perform with music and include dance choreography; men perform in silence with a focus on acrobatics and power.

Where the Split Began: 19th‑Century Physical Culture

The gender split in gymnastics can be traced to 19th-century physical culture movements.

Military Origins for Men

In the early 1800s, Friedrich Jahn in Germany developed Turnen, a form of physical training to prepare men for military service. Apparatus like the pommel horse, rings, and high bar were tools for strength and discipline.

Calisthenics for Women

Women’s training developed separately through Swedish free exercises, which emphasized posture, grace, and coordination. Female exhibitions featured dance-based movement on floor and low beams, prioritizing fluidity over strength.

Olympic Codification

By the time women entered the Olympics in 1928, officials selected events they deemed more “appropriate.”

- The balance beam emerged from earlier free exercises.

- The uneven bars were adapted from the men’s parallel bars and formalized at the 1952 Olympics.

This institutional division became the global standard.

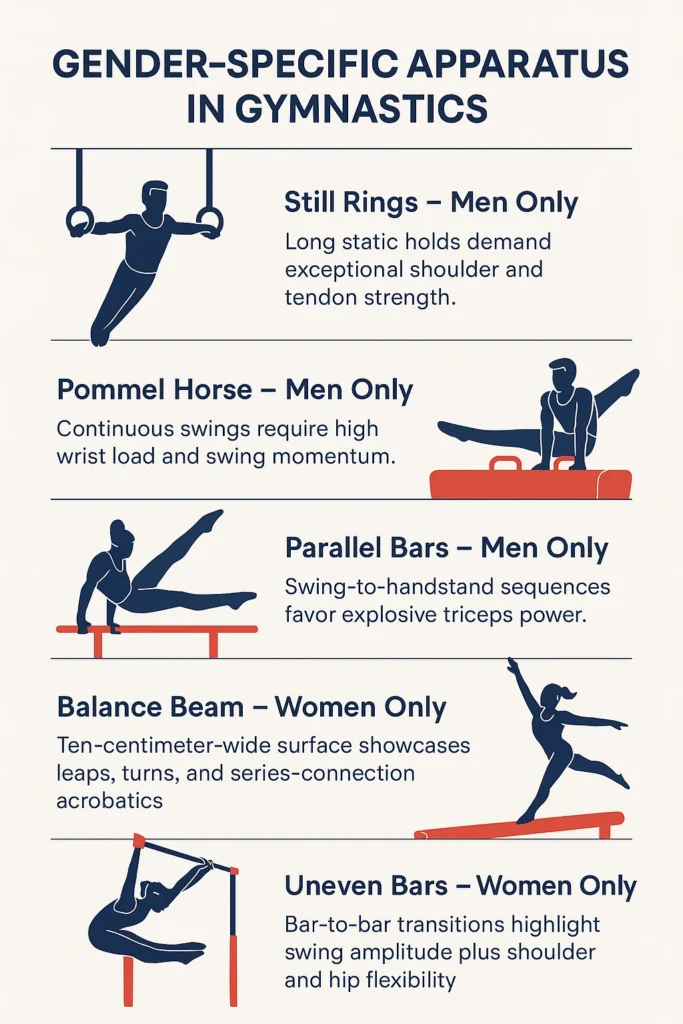

Gender-Specific Apparatus in Gymnastics: Why They Differ

Apparatus Breakdown

- Still Rings – Men only

- Pommel Horse – Men only

- Parallel Bars – Men only

- Balance Beam – Women only

- Uneven Bars – Women only

Now let’s take a closer look at why these events are assigned by gender and the physiological factors behind each one:

1. Still Rings (Men Only)

Why Men Excel:

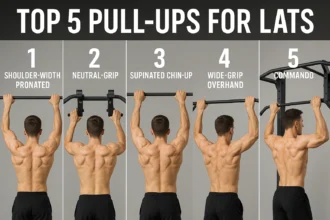

This apparatus involves powerful strength holds like the Iron Cross, Maltese, and Azarian, which require extraordinary shoulder stability and muscular endurance. The routine focuses on minimizing swing and demonstrating complete control in suspended positions.

Physiological Advantage:

Men, on average, have more upper-body muscle mass and broader shoulders, making them better suited for the torsional stress and joint loading involved in ring work. The shoulder girdle structure in males also provides better leverage and tendon support during static strength elements.

2. Pommel Horse (Men Only)

Why Men Excel:

The pommel horse challenges a gymnast’s ability to maintain momentum and rhythm while performing continuous circles, flairs, and scissor elements. High wrist and shoulder loading is necessary to support the body during rapid swings.

Physiological Advantage:

Men’s longer arms, higher center of mass, and stronger wrists allow them to generate better swing mechanics and propulsion. Women, on average, are shorter in stature, which makes straddling the horse and executing large circular movements awkward and less biomechanically efficient.

3. Parallel Bars (Men Only)

Why Men Excel:

This apparatus requires fluid swinging skills, transitions to handstands, and powerful pressing moves. Dismounts often include double-front flips or high-level twists that demand explosive upper-body strength and precision.

Physiological Advantage:

The parallel spacing of the bars corresponds to the typical male shoulder width. Combined with a stronger upper-body frame, men can better perform dynamic and strength-based sequences involving the triceps, shoulders, and core.

4. Balance Beam (Women Only)

Why Women Excel:

A narrow 10-centimeter-wide beam demands pinpoint balance, precision, and elegance. Gymnasts perform a mix of jumps, turns, and series-connected flips, all requiring intense focus and body control.

Physiological Advantage:

Women typically have a lower center of gravity and greater hip flexibility, both of which enhance their ability to stay stable on the narrow surface. Their natural balance and mobility make them more suited to the beam’s requirements for control and artistic presentation.

5. Uneven Bars (Women Only)

Why Women Excel:

Uneven bars showcase high amplitude swings, bar-to-bar transitions, and release moves with a flowing rhythm. It blends power with flexibility, often highlighting smooth pirouettes and regrasp skills.

Physiological Advantage:

The unequal height of the bars caters to the shorter arm span and lighter body weight typical in female gymnasts. These factors make it easier to execute fluid swings and connection elements between bars, something that’s biomechanically harder for taller or heavier athletes.

Shared Events: Vault and Floor Exercise

While most apparatuses are gender-specific, vault and floor exercise are shared across men’s and women’s artistic gymnastics. However, even here, the rules and setup differ.

Vault

Both men and women perform vaults over the same apparatus—known as the vault table—but the height differs:

- Men’s table height: 1.35 meters

- Women’s table height: 1.25 meters

This adjustment reflects differences in average body size, strength-to-weight ratio, and momentum generation, making the vault safer and more suitable for each gender.

Floor Exercise

Both genders perform tumbling passes on the same 12×12 m spring floor, but the presentation diverges:

- Women must perform to music, incorporating dance choreography between tumbling lines.

- Men perform without music, focusing entirely on power, form, and difficulty.

The requirement for music in women’s routines is a carry-over from early 20th-century dance-based calisthenics, which heavily influenced the evolution of WAG (Women’s Artistic Gymnastics). It reflects the sport’s historical emphasis on grace and expressiveness in female performance.

Cultural & Aesthetic Expectations

During the Victorian era, sport was seen as a way to reinforce gender roles:

- Men were to show “masculine power”, so their apparatus emphasized strength, discipline, and military form (e.g., rings, parallel bars, pommel horse).

- Women were expected to express “feminine grace”, so events were chosen for their artistry and elegance (e.g., balance beam, uneven bars, choreographed floor).

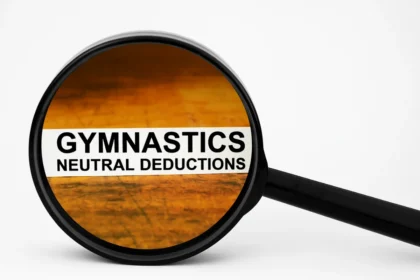

This bias shaped apparatus selection—and still echoes in today’s scoring:

- WAG scoring includes artistry deductions for beam and floor (e.g., dance quality, expression, composition).

- MAG codes offer bonus points for strength elements and hold combinations on rings, parallel bars, and floor.

So even though times have changed, aesthetic expectations from a century ago still influence the rules and values embedded in each event.

Safety & Practicality

Beyond tradition, equipment safety and engineering also justify event separation.

- A 50 kg female gymnast landing a double layout on a men’s high bar or rings, which are stiffer and tuned for heavier impact, would experience excessive joint strain.

- Conversely, a 70 kg male gymnast performing leaps on a 10 cm-wide balance beam would overload its design tolerances for rebound, torsion, and flex.

Each apparatus is calibrated for a specific mass range, impact force, and body mechanics. That’s why manufacturers tailor cable tension, shock absorption, and bar flex based on gender.

In Closing

The gender-specific apparatus in gymnastics weren’t built overnight. While men and women both embody strength, agility, and grace, the sport channels those traits differently through distinct events.

As the conversation around gender, fairness, and flexibility continues, gymnastics may gradually shift. For now, the split persists—not because gymnasts can’t cross over, but because the structure of the sport still reflects its layered, historical roots.